Romani actors and musicians playing Gitano (Romani) characters, as well as Gitano characters portrayed by others outside of the culture, have been present in Spanish theatre since their arrival in the Iberian Peninsula in the fifteenth century. This long tradition can be seen in the multiple forms of Gitano representation throughout history.

Theatre, as the “newspaper of the poor,” and dance, as an expressive form often prone to exoticization, became vehicles of performance for the Spanish Gitano identity, which was ultimately constructed as a celebration of Spanish identity. However, in many ways, an authentic image of the Romani culture remains hidden behind contemporary cultural veils; narratives of conflict, resistance, and negotiation all still need to be acknowledged in the Spanish Gitano theatrical practice.

As a disclaimer, any written record of Gitanos on stage depicts a past time and only registers part of what was lived and experienced. Be it either the existing text Auto das Ciganas by Gil Vicente created in 1521, or a video recording of more recent shows created and seen at the 2018 Flamenco Biennial of Seville, the performances remain memories-in-action that try to reflect on what happened at that particular time, when the event depicted took place.

In order to understand the distinct Gitano performance experience, it’s helpful to look at its history. Using four frameworks, I will attempt to explain the different performance periods. These are: a) the collective representation of Gitanos in religious festivals and rites; b) Gitano characters and stories in theatre as part of a popular demand for Gypsyness; c) Gitano theatre performed by Gitanos, related to the experience of the individual and transgressed expression of the flamenco art form; and d) Gitano theatre as Romani political affirmation. These frameworks show how the Gitano identity in performance art reflects and reproduces the imagery that society demands at the time.

From the Eighteenth-Century Masquerade of the Gitano Nation to the Evangelical Cult

In 1747, the Spanish Gitanos were not yet recognized as citizens with rights. That same year saw a new king rise to the Spanish crown, and the Gitanos of Seville decided to celebrate his coronation with a masquerade. Part of a chronicle of that momentous event explained the masquerade as:

A true story recounting of a curious romance, in which a knight of the city of Jerez de la Frontera breaks the news to another knight of Seville of a masquerade gone wrong, at which the Gitano Nation celebrates the exaltation to the throne of the catholic monarch Fernando the Sixth (God keep him) by gifting him a theatrical interpretation of the conquering of Mexico, and the imprisonment of its Emperor Montezuma, including a dance of young Gitanas…

Gitanos using a mythical narration of the conquest of Mexico to show they were in favor of the new king is pure theatrical ojana! (deception). These same Gitanos, only two years later, would be imprisoned along with nine thousand people as part of a process known as the General Imprisonment of Gitanos of 1749, the objective of which was the genocide of the Romani population of Spain.

After this measure and others like it failed, some of these Gitanos founded the Brotherhood of the Gitanos of Seville in 1753, a religious civil organization that has since participated in the symbolic Holy Week of Seville—a festival and public event consisting of Catholic processions with a very strong counter-reformist theatrical component. This shift from a masquerade to a religious procession shows that Gitanos knew how they could claim their citizenship—through a public demonstration of faith—and that they had the logistical capacity to do so.

In many ways, an authentic image of the Romani culture remains hidden behind contemporary cultural veils.

Gitanos’ participation in religious ceremonies throughout history, whether as dancers or as singers, has been a constant—one that contrasts the persecutory reality they were faced with. It is their deep religious faith that moves them to look for any type of theatrical experience and embraces connection as the cathartic element of community and community rituals and parties.

Whether within the Catholic faith, with plays such as The Word of God to a Gitano(1972) and Come and Follow Me (1982) both by Juan Peña El Lebrijano, or even in the evangelical faith with The Gitanos Sing to God (2010) by Tito Losada, Gitano spirituality has found a way to reconnect the community through theatre.

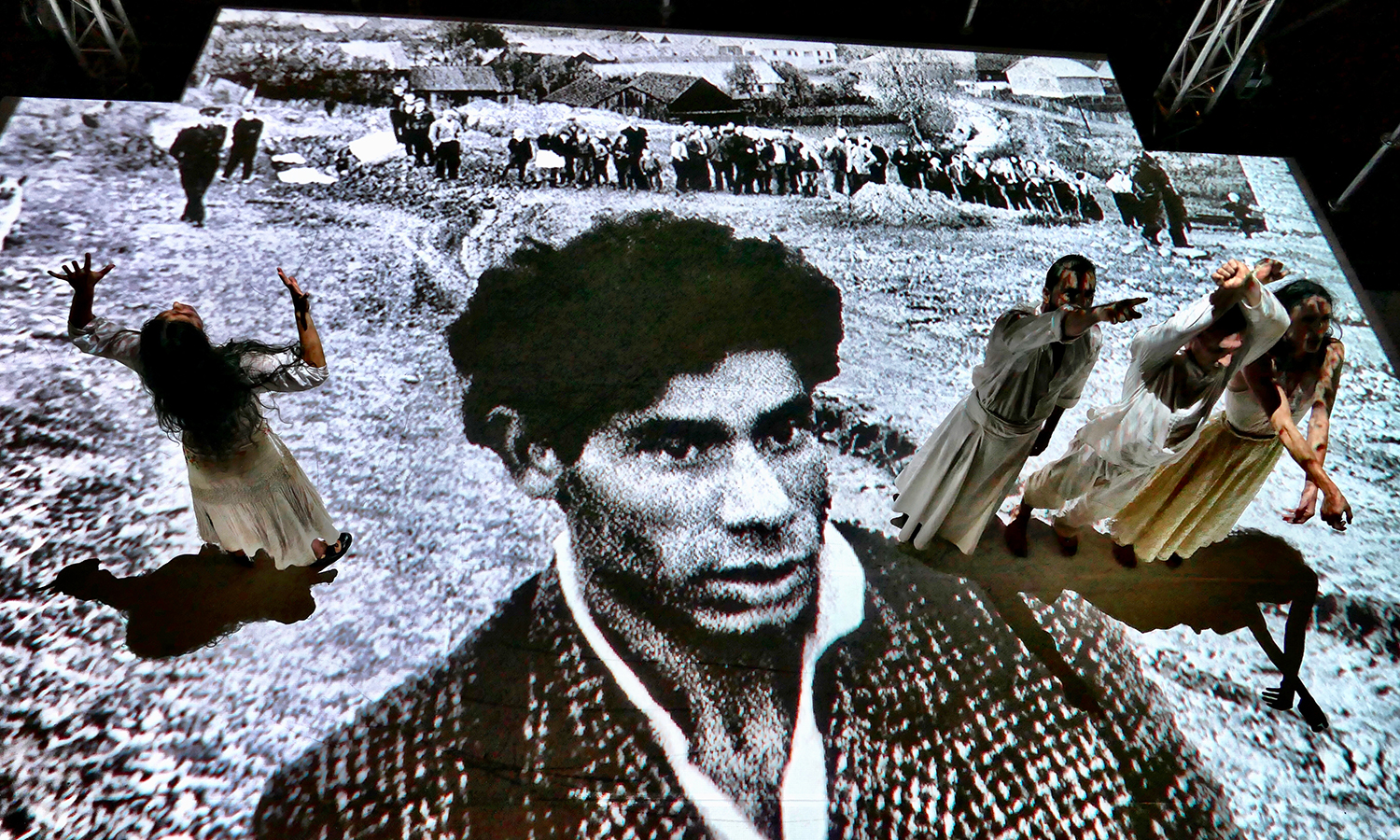

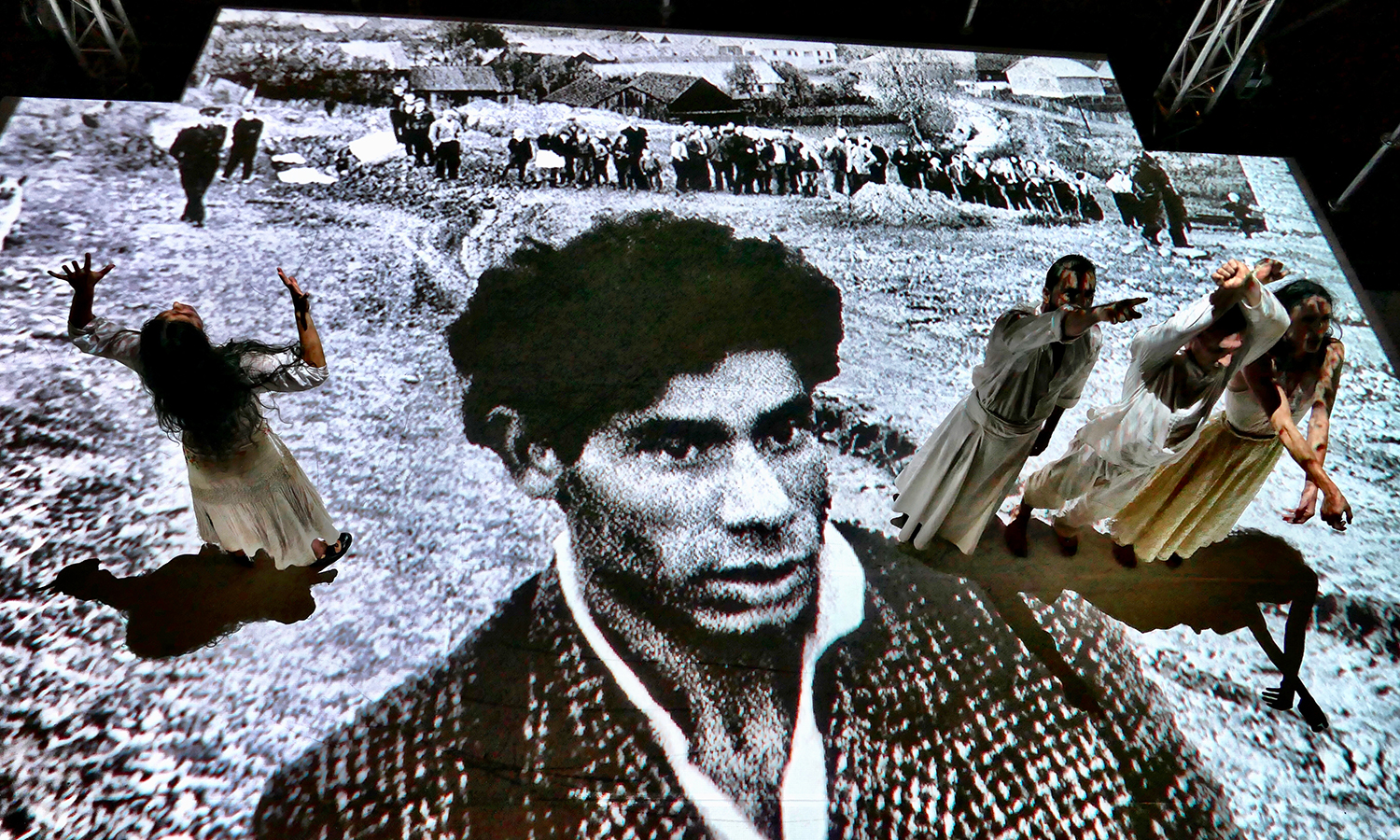

Persecución, co-directed by Miguel Ángel Vargas, Belén Maya, and José María Roca. Photo by José María Roca.

The Theatrical Gitano Expression of Gitanismo of the Nineteenth Century

Although the affinity for Gitanismo—a form of European cultural oppression against Roma people, which lead to an inaccurate Romani stereotype—was born in the second half of the eighteenth century, it was throughout the nineteenth century that it found its place in theatre.

The Gitanismo went from being a disruptive anti-enlightenment and anti-European trend for the wealthy classes of Spain and Europe (where there was specific performance, song, and dance à la Gitano—the Gypsy way) to becoming an almost-obsessive presence in the main theatres of the country through their roles in dance and theatre performances. This was also the time when Gitano characters found places in major historical operas, above all in Carmen by Bizet, based on the 1845 novella by Prosper Mérimée Merimee. This marked the beginning of the path of European obsession with sexualizing Romani women.

There were two popular subgenres whose dramatic structures served as the backbone for what was then known as teatro Gitanesco: the theatrical tonadilla—a short, satirical musical comedy popular in eighteenth-century Spain—and the sainetes—a one-act tidbit, farce, or dramatic vignette with music. There are dozens of works during this period with Gitano characters—with titles and texts in Caló, the Spanish Gitano ethnolect—that feature and enforce crude caricatures of Gitanos, strongly contrasting the real situation of Romani people in Spain. The social imagery of Gitanos in “theatre of the poor” shows unworried Gitanos only interested in love affairs, robbery, and parties. The best-known example is El Gitano Canuto, o día de toros en Sevilla, written in 1816 by Juan Ignacio González del Castillo.

However, all of this theatrical exposure over a century and a half had consequences for Gitano artists, who felt compelled—or socially condemned—to look and perform like these images, something that is still present nowadays for Romani people. However, in more private settings, and thanks to Gitano artists like Lita Claver, who worked in alternative genres like cabaret, the theatrical Gitanismo found one of its counter-narratives by reversing all the happy and naive aesthetics to more dangerous and controversial ones.

The Gitano Individual in the Twentieth Century

The appearance of the flamenco genre in the 1860s, which partially stemmed from teatro Gitanesco, opened the doors to a type of subjective theatrical expression that fought against the stifling corset of mediocre fiction in which Gitanos were inaccurately depicted. This kind of performance took risks with lyrical and individual expression, breaking the fourth wall with a raw and exposed aesthetic. It coexisted with other forms that continued to use the image of the Gitano as “other,” but flamenco helped Gitano artists excel in foreign environments with their own personality.

The reclaiming of the Gitano identity came at the end of the Franco dictatorship, when flamenco became a dignified art form.

During a big part of nineteenth century, many Gitana artists performed anonymously, something depicted in many of the posters from the time period, where they were announced as simply “famous Gitana dancers.” By the end of that century and during a big part of the twentieth century, as flamenco became a highly demanded product—which lead to the professionalization of many artists—many contemporary Gitana artists were leading companies and touring shows as singers, dancers, or entrepreneurs.

Some examples include Pastora Pavón Niña de los Peines, Imperio Argentina, and Carmen Amaya. On top of creating their own work, these artists were featured in classic pieces by non-Gitano writers, like Manuel de Falla and Federico García Lorca—an inclusion, yes, but not the ultimate signifier that would make the Gitano artists accepted as contemporary scenic and musical creators.

Although the situation of Romani people in Spain was still harsh, the creativity and professionalism of the women allowed them to excel in a predominantly male-led world. Carmen Amaya became an international symbol for Romani artists.

Persecución, co-directed by Miguel Ángel Vargas, Belén Maya, and José María Roca. Photo by José María Roca.

Romani Consciousness On Stage in the Twenty-First Century

The idea of Spanish Gitano theatre as political disruption comes from José Heredia Maya’s play Camelamosnaquerar. The reclaiming of the Gitano identity came at the end of the Franco dictatorship, when flamenco became a dignified art form after some years of decadency. This was when theatre groups such as the Teatro Estudio Lebrijano and La Cuadra de Sevilla, under the influence of Grotowski’s “poor theatre” philosophy, started to break censorship through the use of flamenco, and when aesthetics around rituals and agriculture became almost stylistic constants.

Teatro Gitano, recognized as theatre with political significance, created a process and kind of work that Gitano theatremakers still follow. Watching Camelamos naquerar,Romani audiences experienced catharsis, witnessing for the first time the true representation of their history and struggle. This led to the creation of many Romani advocacy organizations.

The work of Belen Maya in Romnia, Celia Montoya in Tras-pasos.Light and Memory to the Forgotten Ones, Paco Suárez in Ithaca, Manuel de Paula in Chachipén, Sonia Carmona in De profunda dignitatis, and even my own work in Gilǎ falls within this style. Each one of us is making a proud affirmation of resistance inherent to being Gitano, to being Roma.

These works have another common element: they are the result of collective processes aimed at pointing out both the hurtful and unresolved problems in society, mainly the inherent racism in Spain and Europe, and promoting the rich diversity of Romani identities and stories on stage and the debate around their importance.

Though there are many more examples of how Gitano performance has been used and seen throughout history, these frameworks act as a way to start recognizing Gitanos’ theatrical history and promote the re-imagining of the Gitano identity.

THOUGHTS FROM THE CURATOR